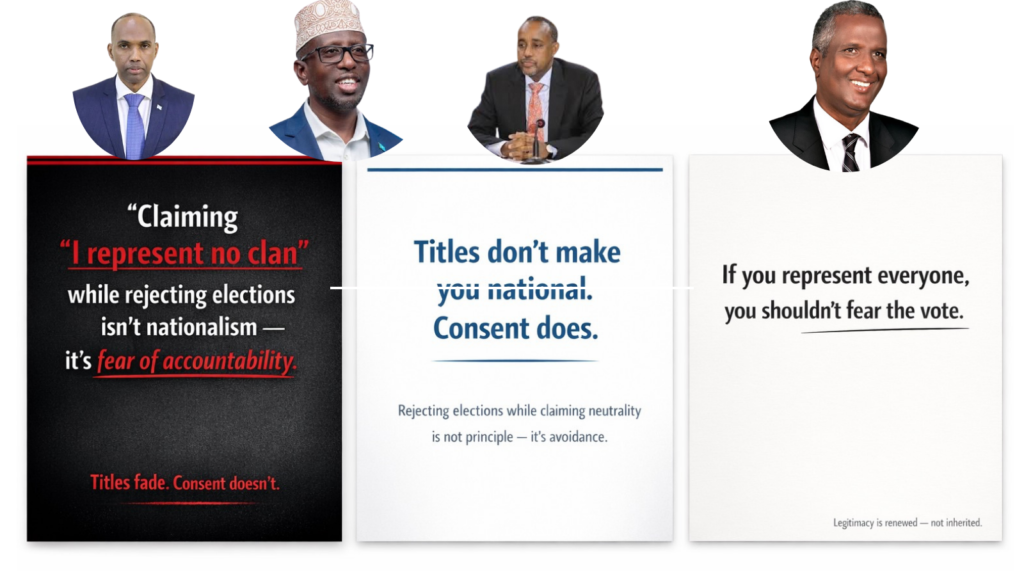

Every time Somalia’s election system shifts, you can almost predict the response. A former senior official steps forward and says something along the lines of: “I was Prime Minister. I represent no clan.” On the surface, it sounds reasonable. Even admirable. But it rarely appears at random moments. It usually shows up right when the rules of the game begin to change—when politics starts moving away from closed negotiations and toward broader public participation.

That timing matters.

No Somali politician rises in isolation. Power is built slowly and socially—through people, elders, favors, alliances, and long conversations behind the scenes. Yes, the office of Prime Minister is national in law. But Somali politics does not live inside legal language. It lives in neighborhoods, family meetings, mosques, and the quiet calculations people make about trust and loyalty. When election systems move from predictable deals to open competition, many of the same figures suddenly begin questioning legitimacy.

This isn’t accidental. And it isn’t just hypocrisy either.

To understand why compromise repeatedly collapses in Somali politics, it helps to stop framing it as a moral failure. This is less about bad intentions and more about how the system itself shapes behavior.

Why Compromise Feels Dangerous

In countries with strong institutions, compromise is survivable. You lose an election, regroup, and return another day. Opposition is protected. Political life continues. Somalia doesn’t yet offer that kind of safety.

Here, power is fragile. Losing office often means losing relevance, access, and protection. In that context, compromise doesn’t feel like maturity—it feels like risk. Giving ground today can mean disappearing tomorrow. That reality pushes politicians toward rigid positions, even when flexibility might seem wiser from the outside.

It’s not always about ego. Sometimes it’s about survival.

Clan as a Safety Net, Not a Slogan

Many Somali politicians publicly distance themselves from clan politics. Privately, clan still functions as a fallback system. It offers protection after defeat, relevance when power fades, and leverage when negotiations return. For many, clan isn’t an ideology—it’s insurance.

Real compromise would require deep trust that institutions can protect political losers. Somalia’s institutions are improving, but they are not yet strong enough to fully replace informal guarantees. This is why claims of being “above clan” often collide with resistance to systems that weaken clan-based bargaining. The contradiction isn’t random. It’s structural.

Why Elections Make Elites Nervous

Older political arrangements favored familiar faces, controlled negotiations, and outcomes that could be managed. Newer election models introduce voters, visibility, and uncertainty. That changes the risk calculation.

Elite bargaining rewards experience and connections. Popular participation rewards credibility and public trust. Not all political capital transfers smoothly between the two. This is why opposition to elections is often framed as concern for legality or stability—because openly admitting fear of exposure is politically costly.

Security as a Permanent Pause

Security concerns in Somalia are real. No serious observer denies that. But politically, insecurity has also become a convenient pause button. If instability can indefinitely delay elections, then violence ends up controlling the political calendar.

Freezing politics in the name of security may sound cautious, but over time it becomes something else. It allows fear to replace progress. No country defeats insecurity by letting it permanently override political development.

Do Elections Really Divide Clans?

It’s often said that elections divide clans. That argument flips reality on its head. Clans were politically divided long before ballots existed. Elections don’t create division—they expose it.

What makes elections uncomfortable is not division itself, but visibility. They replace assumed legitimacy with measurable consent. For leaders used to negotiated authority, that exposure can feel threatening.

The Quiet Fear Beneath It All

At the deepest level, resistance to compromise is driven by fear of irrelevance. Titles expire. Access fades. Influence shrinks. What remains is whether people still choose you when given the chance.

That question can’t be negotiated away. And it’s one many politicians would rather avoid.

Why Compromise Rarely Wins

Strategically speaking, Somali politics often operates like a zero-sum game with weak enforcement. Winners gain most of the benefits. Losers risk political extinction. In that kind of system, refusing to compromise can be a rational choice.

Cooperation doesn’t emerge from speeches or good intentions. It emerges when incentives change.

Making Compromise Possible

If compromise keeps failing, the solution isn’t shaming politicians or demanding moral transformation. The solution is redesigning the system so that losing is survivable.

That means:

- Losing an election doesn’t end political life

- Opposition rights are protected in practice, not just on paper

- Electoral bodies and courts are genuinely independent

- Political transitions are predictable, not sudden shocks

- Former leaders have dignified roles outside executive power

When loss becomes safe, compromise becomes rational.

A Real Way Forward

Somalia won’t move forward by declaring itself post-clan or by pretending fear doesn’t exist. Progress will come when political systems allow disagreement without destruction, loss without exile, and competition without panic.

Nationhood isn’t declared. It’s practiced.

Legitimacy isn’t inherited. It’s renewed.

Titles fade.

Consent still matters—after the vote, not before it.